“The Unwanted” by Michael Dobbs is a riveting and unfortunately true story of how the world turned their back on Jewish families seeking to escape Nazi Germany. Although many would like to compare it to the current day, the fact is that the book’s account of the early years of World War II does not echo today’s policies. After reading this book, anyone that compares the past and present should be ashamed. As the book illustrates these were true asylum seekers.

The problem thwarting the Jewish escape was mainly the low refugee quotas. At a time when the American public was deeply isolationist, xenophobic and anti-Semitic, U.S. officials dragged their feet or denied visas.

Dobbs quotes American journalist Dorothy Thompson, “A piece of paper with a stamp on it was the difference between life and death.” Using the village of Kippenheim as a sample population, he shows the tragic consequences of an unresponsive refugee policy. This small village is located on the edge of the Black Forest, not far from the French/German border of the Rhine River. A place where Jews and Christians lived peacefully with each other for generations, notably the town’s synagogue was right down the street from the Catholic Church.

Dobbs writes how anti-Semitism seemed to be confined to cities and towns, “For many Christian Kippenheimers, anti-Semitism was more a matter of class resentment than racial hatred… A cultural and psychological gulf developed between the Christian farmers and the Jewish tradesmen,” that did not manifest itself into much violence.

Yet, everything seemed to change after Kristallnacht in late 1938, when Jewish homes, hospitals, synagogues, businesses and schools were ransacked and destroyed. The Nazis claimed it was a supposed “spontaneous protest” against “murderous” Jews. There was a senseless roundup of Jewish men, a signal to those who were paying attention, that Germany was not safe. Dobbs writes, “Any doubts about what they should do were swept away in an instant. A single hope remained: emigration.”

Dobbs delves into the lives of a few families from the village and the attempts they made to escape. Many were successful and were able to leave before and slightly after the breakout of war on Sept. 3, 1939. Several Kippenheimers made it to Marseille and then on to the United States via Morocco. But most of the remaining Jews were sent to Gurs, a holding camp in the southwest part of France, and from there to the killing concentration camp, Auschwitz. Readers find out how 6,500 Jews were deported, where roughly one in four died in the deplorable French camps — four out of 10 were sent to Auschwitz.

The book recounts how the wait for visas turned deadly for Kippenheimers Gerda and Momo Auerbacher. With their papers stamped “Immigration to the United States pending,” they were crammed into railroad cars and taken to the final stop on their life’s journey: Auschwitz. Another village couple, Max and Fanny Valfer were finally granted visas in August 1942, just weeks after the Germans shifted their policy toward Jews from expulsion to extermination. The Valfers were deported “to the east” in the fall of 1942 and murdered at Auschwitz.

Dobbs tried to be fair-minded when he showed both opinions regarding the American response to the Holocaust and whether more could have been done to save the persecuted Jews. Dobbs quotes David Wyman who wrote a book “The Abandonment of the Jews,” “Both the president (FDR) and the Congress had failed the test of leadership. The State Department was guilty of ‘outright obstructionism.’ The press was also complicit.”

Roosevelt’s passivity while the European Jews were massively being annihilated was deplorable. He did nothing while the St. Louis, a ship carrying Jewish refugees from Germany, was denied access. He did nothing to gather support for the Childrens’ Jewish Refugee Bill, and allowed men like Breckinridge Long in charge of the State Department’s refugee programs, to remain in office instead of firing him. This hands-off policy proved Hitler correct when he said that no one wants the Jews.

Dobbs reminds people that the six million are not just a statistic, but actual human beings. They suffered atrocities, mass murder, crimes against humanity, and/or genocide. Readers will understand through these individuals their desperate struggle to survive at a time when the world abandoned them.

Elise Cooper: I know that some reviews might use your book to compare it to the present-day situation. How do you feel about that?

Michael Dobbs: This is a book about history, not about the modern-day politics. I did not want to make a judgment but allow readers to draw their own conclusions based on the facts. As a writer I believe in show, don’t tell.

EC: Why did you decide to write the book?

MD: I work for the Holocaust Museum. To celebrate the 25th Anniversary, they have a new exhibit, “Americans and the Holocaust.” I helped with the research that dealt with the refugees and their immigration to the U.S. I want to connect the abstract with the impact it had on ordinary people. I chose the village of Kippenheim because it had a substantial Jewish community that tried to emigrate to the U.S. The families I write about had different experiences: some succeeded getting to America, and some did not.

EC: You also discuss the different attitudes towards the Jews?

MD: There were different perspectives regarding the Jews in Kippenheim. Some villagers were outright Nazis like the postmaster who waged brutal campaigns. Some were sympathetic and helped such as Anna Kraus who sold milk and eggs to the Wachenheimer Family and visited them late at night when the rest of the village was asleep. Yet most just put their heads down.

EC: Do you think that many Jews stayed too long before trying to get out?

MD: I think the younger Jews had fewer ties to Germany and saw the writing on the wall sooner. But after Kristallnacht everybody understood that it was no longer safe for a Jew to live in Germany. The decrees robbed most of them of their wealth and they needed to rely on charity to get out of the country.

EC: What do you want the reader to get out of your book?

MD: I want everyone to understand the human dimension where real lives are at stake. I tried to show what it was like to be a refugee trying to emigrate to the U.S. This included all the harrowing aspects that they went through, the bureaucratic nightmare. I wanted to show the political debate at the time and the issues that went on with the various sides.

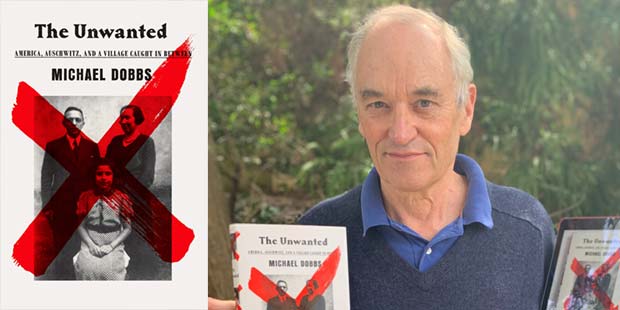

Deportation of a Jewish family, Kippenheim, 1940.